The Most Sacred Property

Note: this is a guest blog post co-authored by Bryan Austin & Christian Cotz.

Two hundred and seventy years ago, a colossus of critical thinking was born.

James Madison, regarded by history as the Father of the Constitution and architect of the Bill of Rights, usually sits happily in the shadow of the other figures that make up the pantheon of Founding Fathers. Though he never desired the spotlight, Madison ensured he was in the room for most of early America’s important political debates and, more often than not, engineered the winning arguments.

James Madison portrait by Gilbert Stuart ~ 1805-1807

Indeed, the political accomplishments of James Madison are enough to fill volumes, and they have, but on this particular birthday, I want to highlight one goal he never deviated from achieving in his forty-year career: the liberation of the human mind.

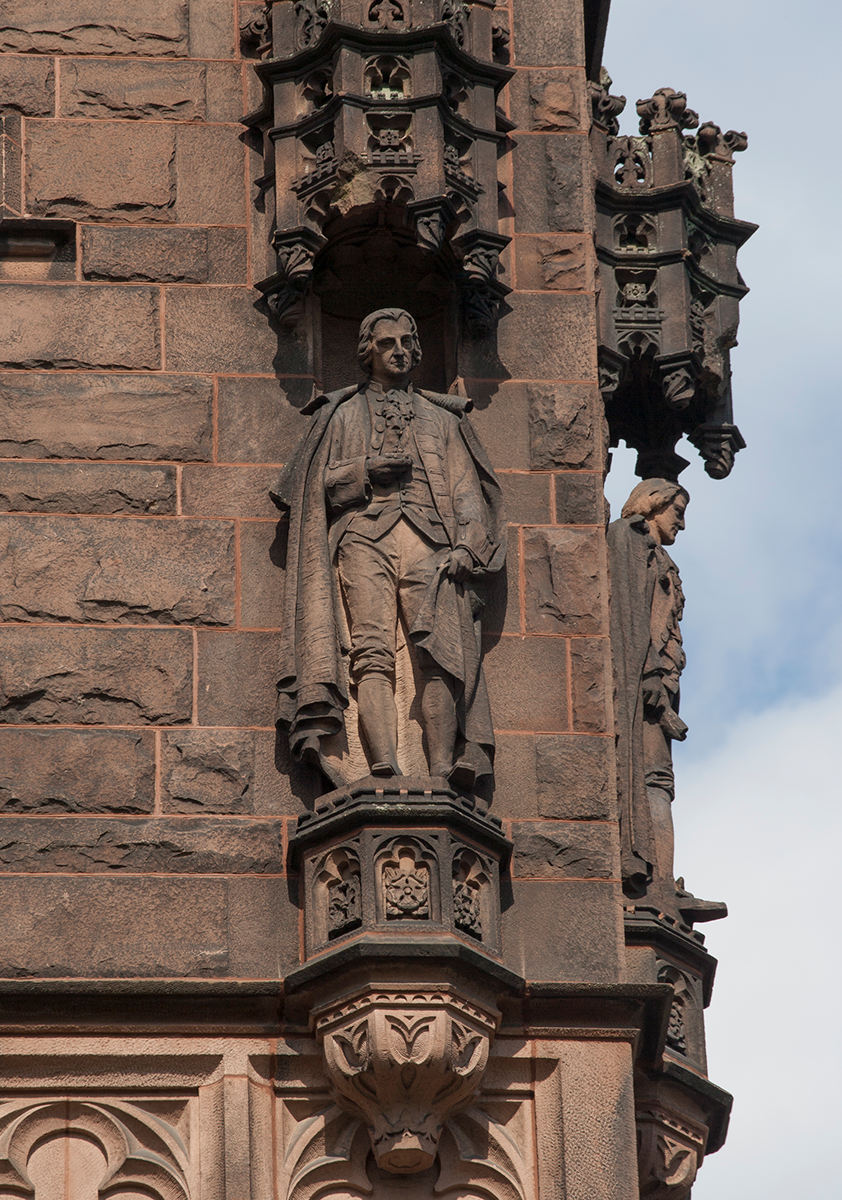

James Madison, Class of 1771 statue at Princeton University

From a young age, Madison had a ravenous appetite for knowledge. By eleven, he had read the entirety of his father’s small library, and he spent his adolescence in a small and demanding private boarding school.

By the age of twenty-one, he could read in seven languages, and he had completed a five-year education at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) in just three short years. He was an eager student of revolutionary new ways of thinking – a rapt creature of the enlightenment.

After college, Madison moved back in with Mom and Dad and struggled to decide what to do with his life. Ironically, a life in politics was something he never envisioned himself pursuing. He was depressed. He was ill. He wrestled with how to apply the diverse lessons he learned in college to a life he could derive worth from. Complicating matters, his view of his native home of Virginia and its economy had grown jaded. He wrote about “the dreadful fruitfulness of the original sin of the African trade,” though, even later, he never put much political effort into ending slavery, nor freeing himself, personally, from its profits, or the people he owned from their enslavement. Still, as a young man, Madison struggled to square his Revolutionary and Enlightenment values with the institution of slavery and found only hypocrisy.

James Madison’s Montpelier plantation house, home to ~100 enslaved people at any one time during Madison’s lifetime

Eventually, Madison was compelled to action by the pervasive religious bigotry that existed in the colony of Virginia. “Religious bondage shackles and debilitates the mind and unfits it for every noble enterprise, every expanded prospect” he wrote. As Revolution against England threatened the horizon, Madison penned a note to his classmate from Pennsylvania, William Bradford:

“I want again to breathe your free Air. I expect it will mend my Constitution & confirm my principles….but have nothing to brag of as to the State and Liberty of my Country. Poverty and Luxury prevail among all sorts: Pride ignorance and Knavery among the Priesthood and Vice and Wickedness among the Laity….There are at this time in the adjacent County not less than 5 or 6 well meaning men in close Gaol for publishing their religious Sentiments which in the main are very orthodox….I leave you to pity me and pray for Liberty of Conscience to revive among us.”

Religious liberty – the liberty of conscience, as Madison called it – became the battleground that young Madison planted his flag on, and, in 1776, while the Revolutionary War began in earnest, Madison’s personal campaign for the liberation of man’s mind began simultaneously.

Madison was appointed to be one of the youngest delegates to the 5th Virginia Convention. In the spring of 1776, along with resolving for independency and crafting a new constitution for the Commonwealth of Virginia, Madison scored his first political win and carved a path for the eventual separation of church and state in Virginia. He drafted an amendment to the Virginia Declaration of Rights and changed the “toleration” of religious opinion into the “free exercise” of it “according to the dictates of conscience.” This small victory echoed far louder in the ensuing years with Jefferson’s famous Statute for Religious Freedom. While that particular bill was tabled for over a decade, fierce debates raged over the role of government in managing people’s minds and beliefs. And through it all was Madison, championing the cause of the free mind. Finally, in 1786 he orchestrated the passage of his friend’s bill and upon its success, wrote to Jefferson in France, “I flatter myself we have in this country extinguished forever the ambitious hope of making laws for the human mind.”

Madison as a 32-year-old Congressional delegate, 1782 portrait by Charles Willson Peale

For Madison, the mind was sacrosanct because it is only through free and independent thought that society evolves. So, when it was time to limit the powers of the federal government by providing a bill of rights that would protect those unalienable rights that Jefferson had written about a decade earlier, Madison believed that paramount among them were the right to think, and to act on our thoughts. It is no wonder, then, that his First Amendment, which protects the freedoms of religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition, can all be distilled into his firm and resolute belief, that “Conscience is the most sacred of all property.”

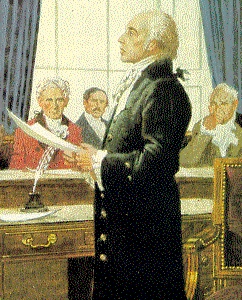

Madison reading his Bill of Rights to Congress.

Courtesy: University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law.

Two hundred and seventy years after his birth, the legacy of Madison’s ideas can be seen throughout the world. What began as a fight against religious oppression has transformed into something far more beautiful: the freedom to think, to imagine, to create, to innovate, and to express. It has allowed the voiceless to speak, the downtrodden to stand. It has ennobled the cause of education and reared a society that takes alarm at any attempt to censure mankind’s capacity to think.

On this, his 270th birthday, there can be no finer gift to give Madison than our commitment to a nation where the freedom of thought is one of the most nurtured and essential qualities of an American citizen.

Bryan Austin is a writer, actor and storyteller with over fifteen years of professional experience in the world of performing arts. He is the resident James Madison scholar for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and his portrayal of Madison has been seen across the country by audiences of students, judges and statesmen.

Christian Cotz is the CEO of the First Amendment Museum.

Related

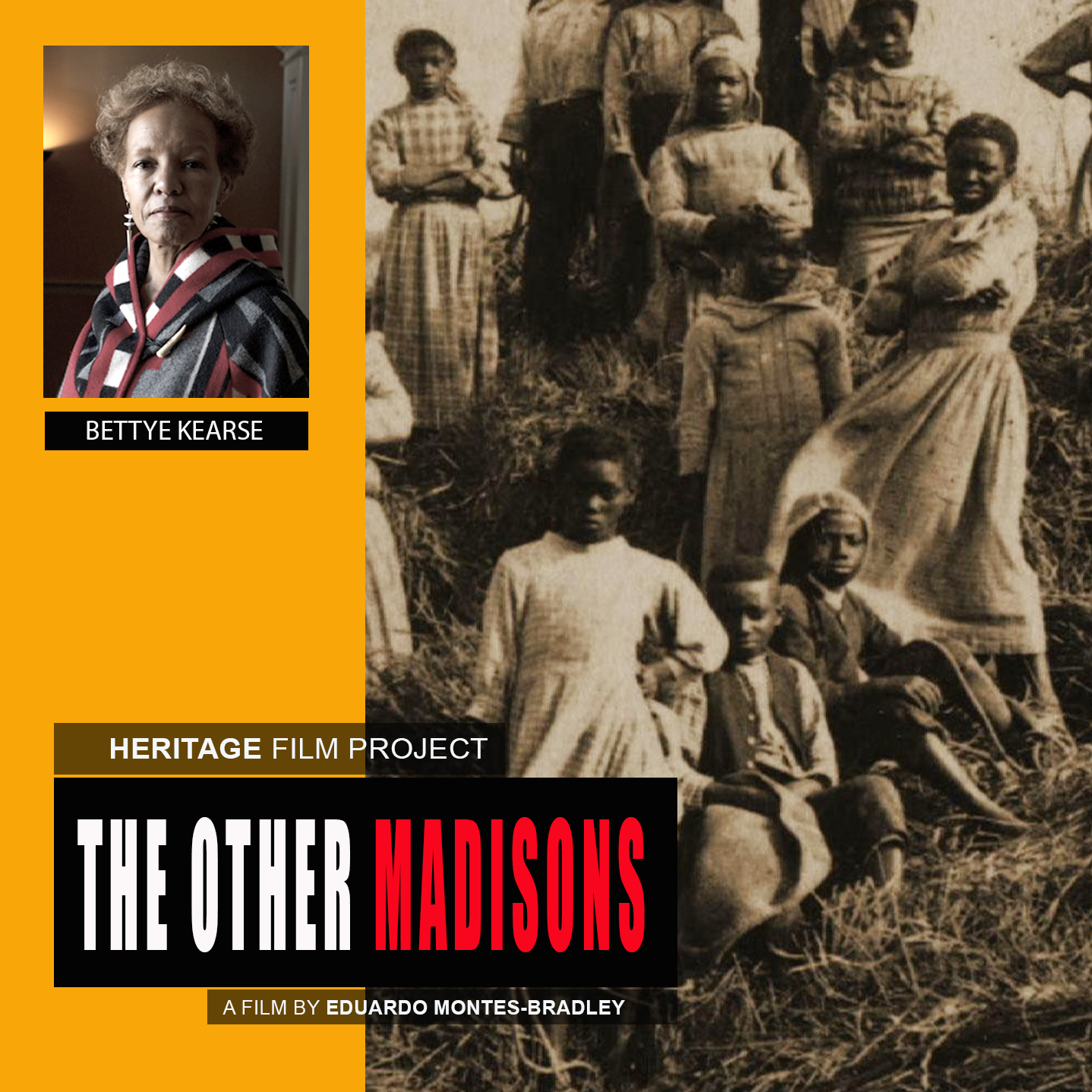

“The Other Madisons” with a Q&A afterward with author Bettye Kearse and filmmaker Eduardo Montes-Bradley.

This documentary film by Montes-Bradley is based on the memoir The Other Madisons: The Lost History of a President’s Black Family by Kearse. Learn more >