The most successful and renowned nineteenth-century American political cartoonist was German immigrant Thomas Nast.

Nast is most famous for his 160 political cartoons attacking the criminal characteristics of Boss Tweed, a politician notable for controlling New York’s corrupt Democratic political organization, Tammany Hall.

The modern image of Santa Claus and the elephant representing the Republican party were Nast creations. Nast’s work represents the final maturation of the political cartoon into the form that we are familiar with today.

Political cartoons of this era were mostly published in magazines such as Harper’s Weekly, Puck, Judge, and more – although many were also published in newspapers.

Click on each image to enlarge.

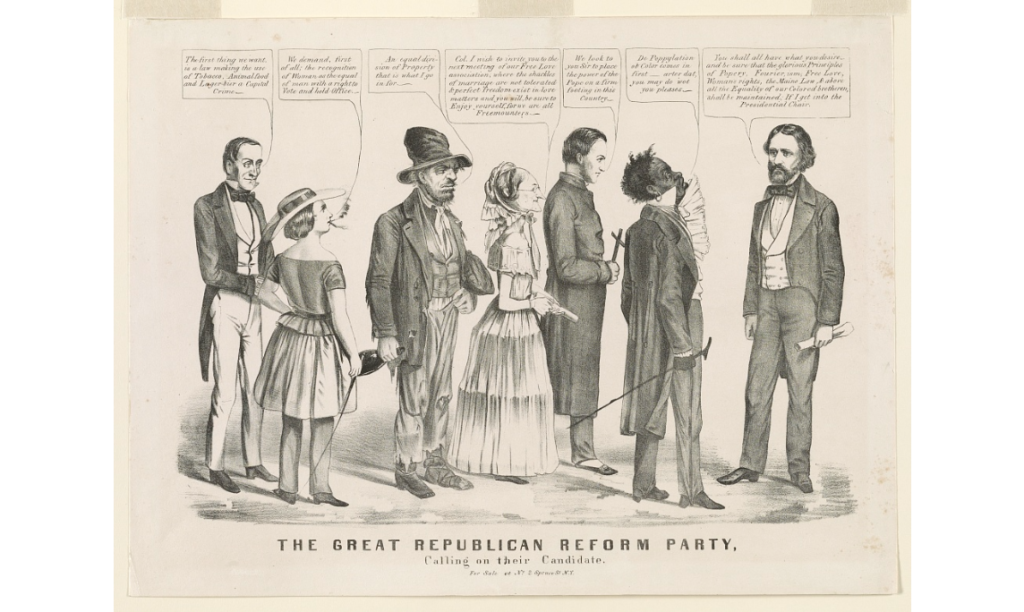

The Great Republican Reform Party

Louis Maurer, 1856, for Currier and Ives, New York, New York

The Republican Party of the mid-nineteenth century was composed of a wide array of reformers and disparate groups. This cartoon mocks the Republicans by lampooning “typical” Republicans who are depicted here calling on their candidate for the 1856 United States presidential election, John C. Frémont.

From left to right, these “typical” Republicans are an obnoxious prohibitionist, a radical feminist, a squalid Socialist, a homely free love advocate, a Catholic, and a racist black stereotype. They face Frémont who says, “You shall all have what you desire,” including “the Maine Law,” which refers to the first prohibition law in the United States enacted by the state of Maine.

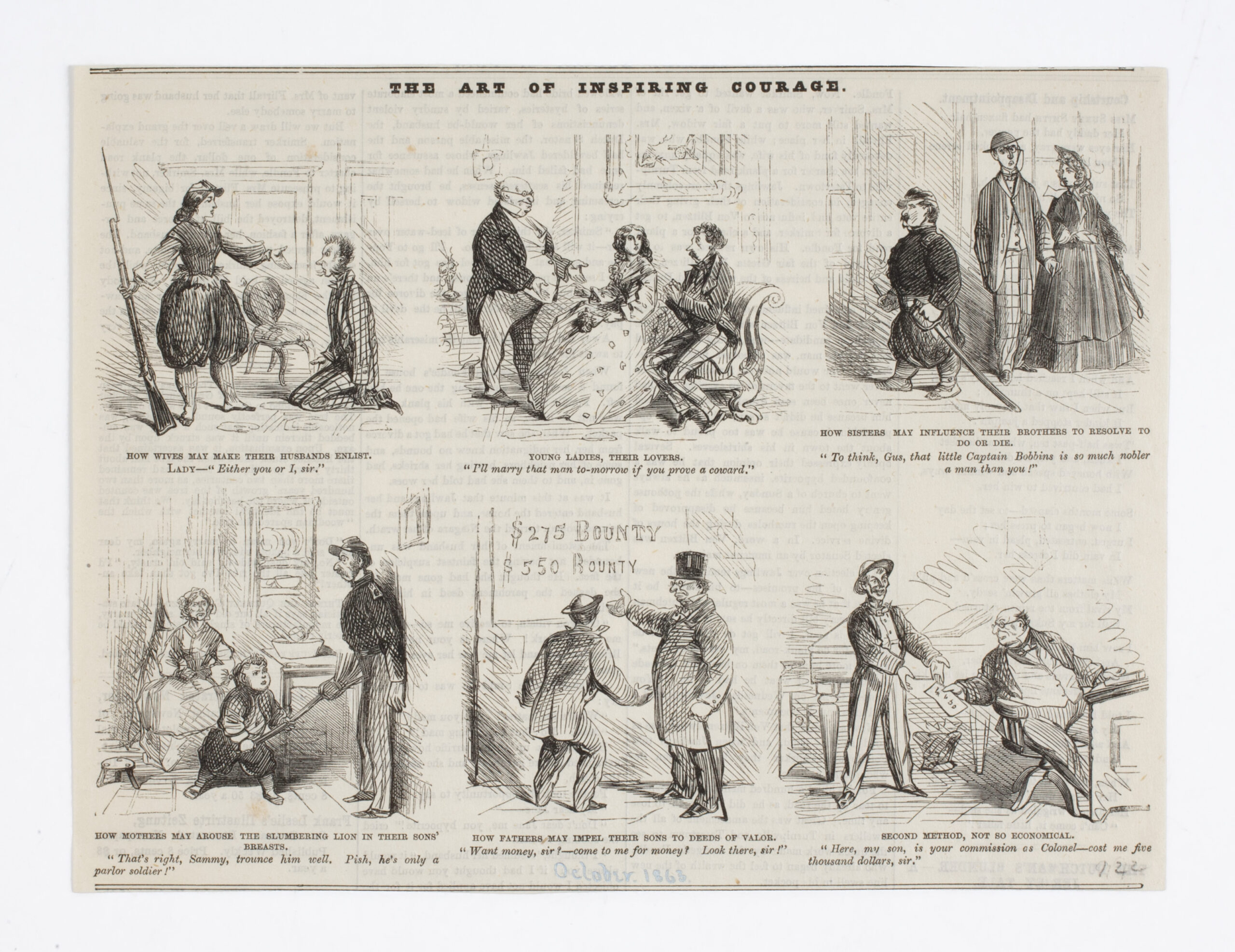

The Art of Inspiring Courage

Frank Leslie, 1863, for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, New York, New York

This cartoon sardonically depicts how family members can inspire or pressure their husbands, sons, or brothers to enlist in the Union Army during the Civil War.

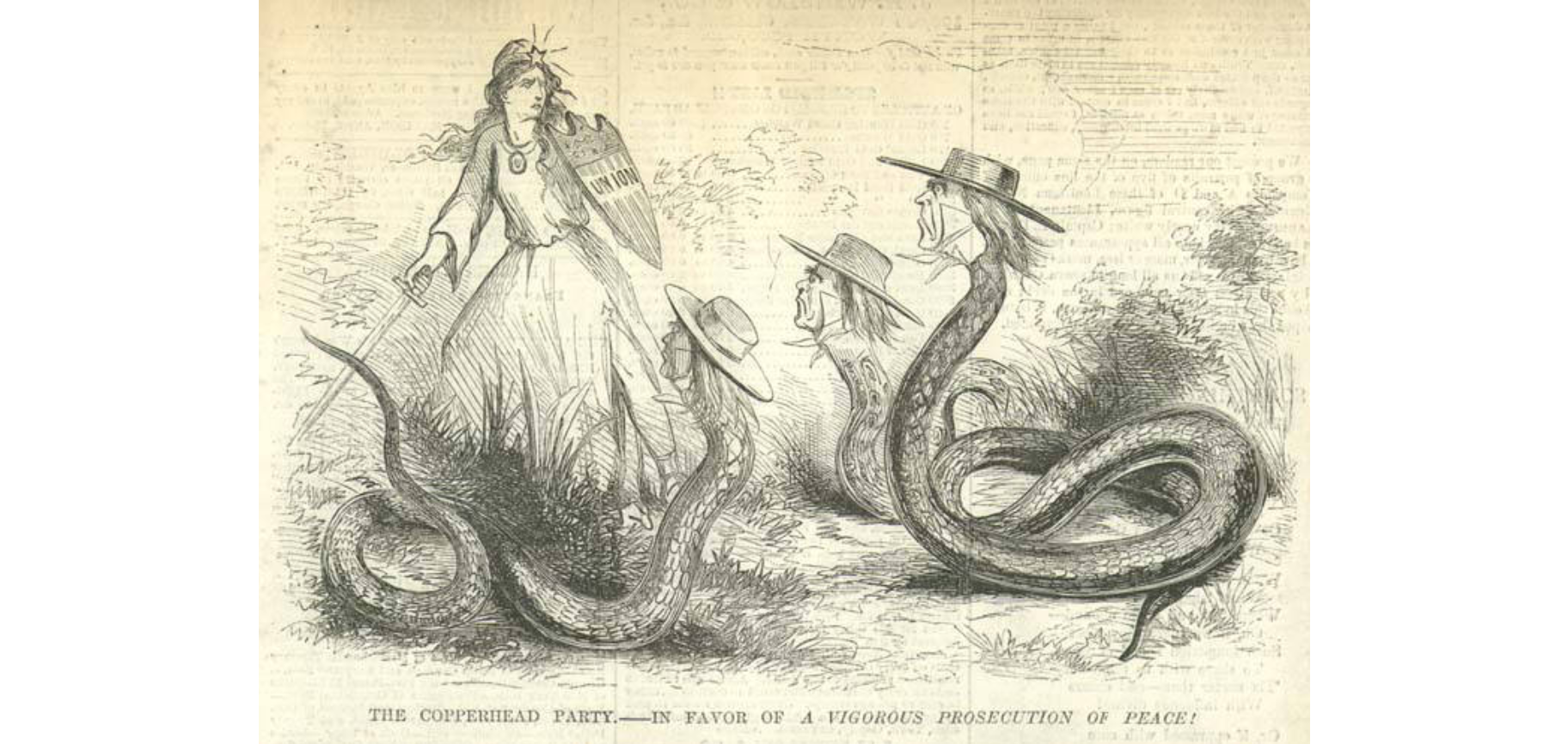

The Copperhead Party – In Favor of a Vigorous Prosecution of Peace!

Artist unknown, 1863, for Harper’s Weekly, New York, New York

Columbia, a female personification of the United States, fends off “the Copperhead Party,” or the Northern Democrats who opposed the Civil War and supported peace with the South, depicted as snakes with human heads. The Copperheads’ “vigorous prosecution of peace” is denounced in this cartoon as peace only at the expense of the Union.

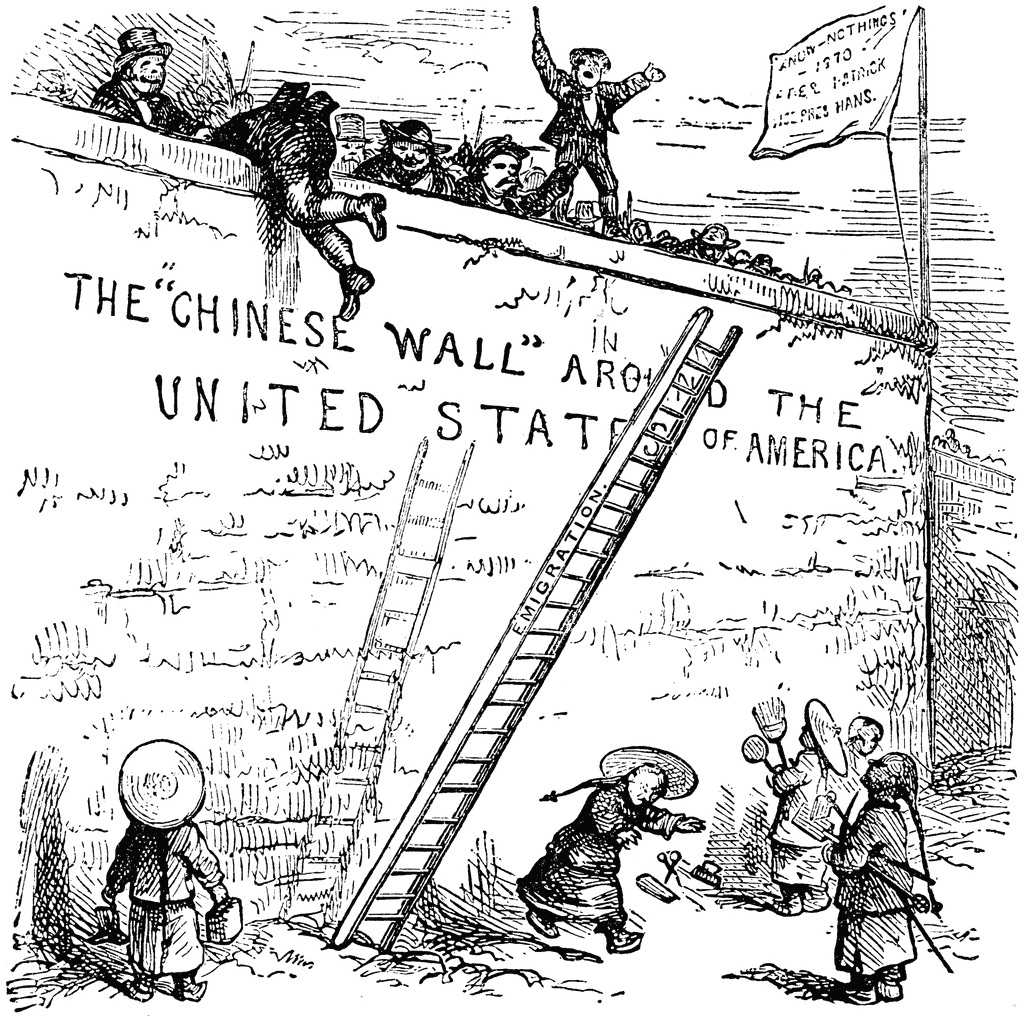

Throwing Down the Ladder by Which They Rose

Thomas Nast, 1870, for Harper’s Weekly, New York, New York

This cartoon depicts anti-immigrant Americans, under the banner of the “Know-Nothing Party,” a nineteenth-century nativist political party, throwing down the ladder “by which they rose” in an attempt to deny Chinese immigrants entry into the United States. The hypocrisy of the descendants of immigrants denying citizenship to new Chinese immigrants is on full display in this biting political cartoon.

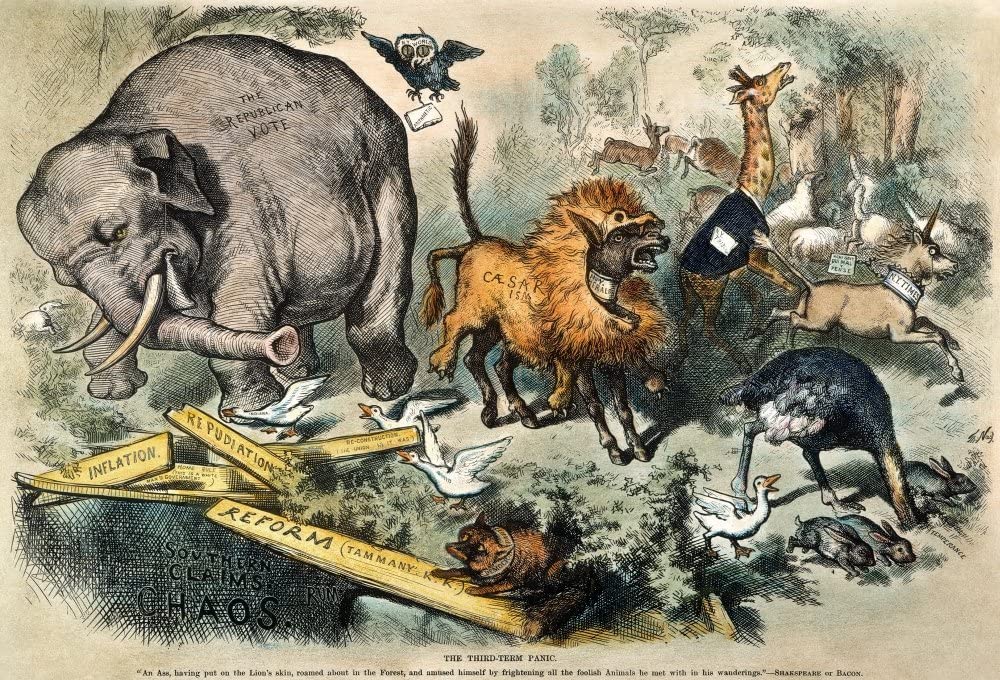

Third Term Panic

Thomas Nast, 1874, for Harper’s Weekly, New York, New York

Cartoonist Thomas Nast featured an elephant for the first time in 1874 to represent the Republican vote. He rendered the animal, unsure of its weight, plodding through planks representing its party platform. The animals in this cartoon, including the Republican elephant, flee in terror from a donkey, representing the Democratic party, disguised under lion’s skin and wearing a collar that says “N.Y. Herald.” The New York Herald was a newspaper critical of the Republican party.

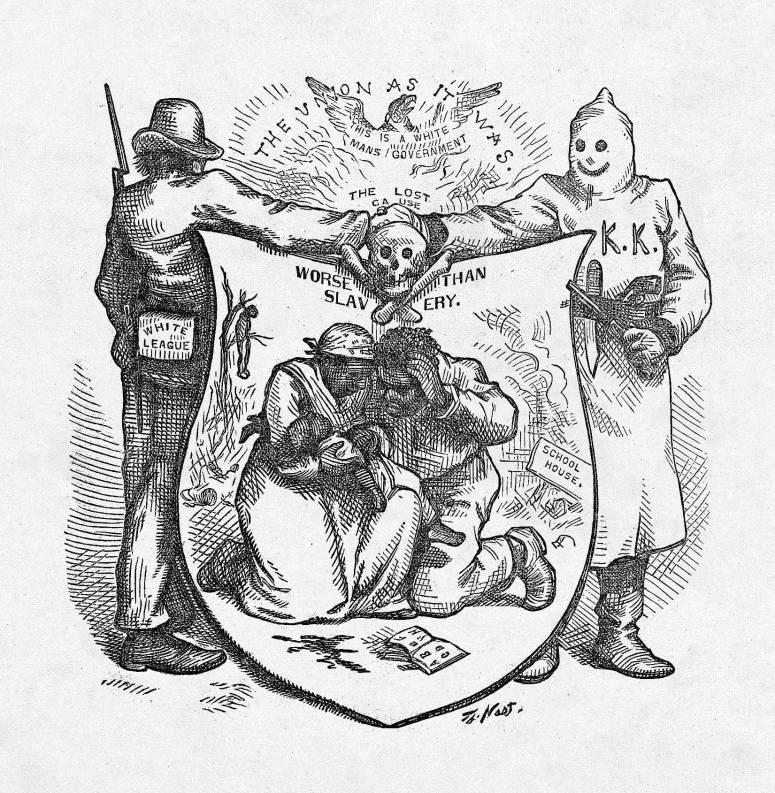

The Union as it Was

Thomas Nast, 1874, for Harper’s Weekly, New York, New York

A member of the Ku Klux Klan and a member of the White League shake hands atop a skull and crossbones. It rests above a black woman and man huddled over their dead child. In the background, a schoolhouse burns, and an African American is lynched. This cartoon is a chilling indictment of white resistance to Reconstruction and a frank depiction of the condition of formerly enslaved people in the South during the years after the Civil War.

The Tournament of Today

F. Graetz, 1883, for Puck Magazine, New York, New York

One of the defining tensions of the late nineteenth century was between labor and industry. This cartoon depicts the forces of monopolizing capitalism jousting against the forces of organized labor. Depictions of captains of industry watch the tournament on the left while a crowd of anonymous workers watches on the right.

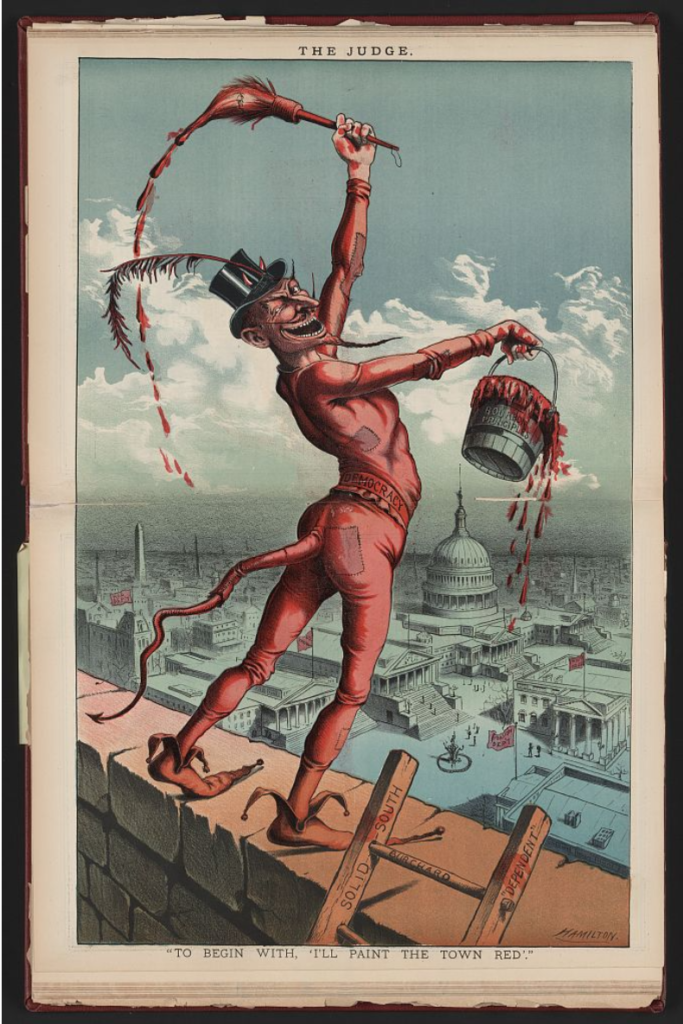

To Begin With, I’ll Paint the Town Red

Grant Hamilton, 1885, for Judge Magazine, New York, New York

The Devil, wearing a belt that says “Democracy” and holding a bucket of red paint labeled “Bourbon Principles,” perhaps representing blood, stands above Washington D.C. Although originally a nationwide movement, the term “Bourbon Democrat ” eventually became a moniker for Reconstruction-era Democrats, many of them Confederate veterans, who came back to power after the overthrow of Reconstruction. The Bourbon Democrats implemented new measures to ensure white supremacy and used both democratic and violent methods to gain power.

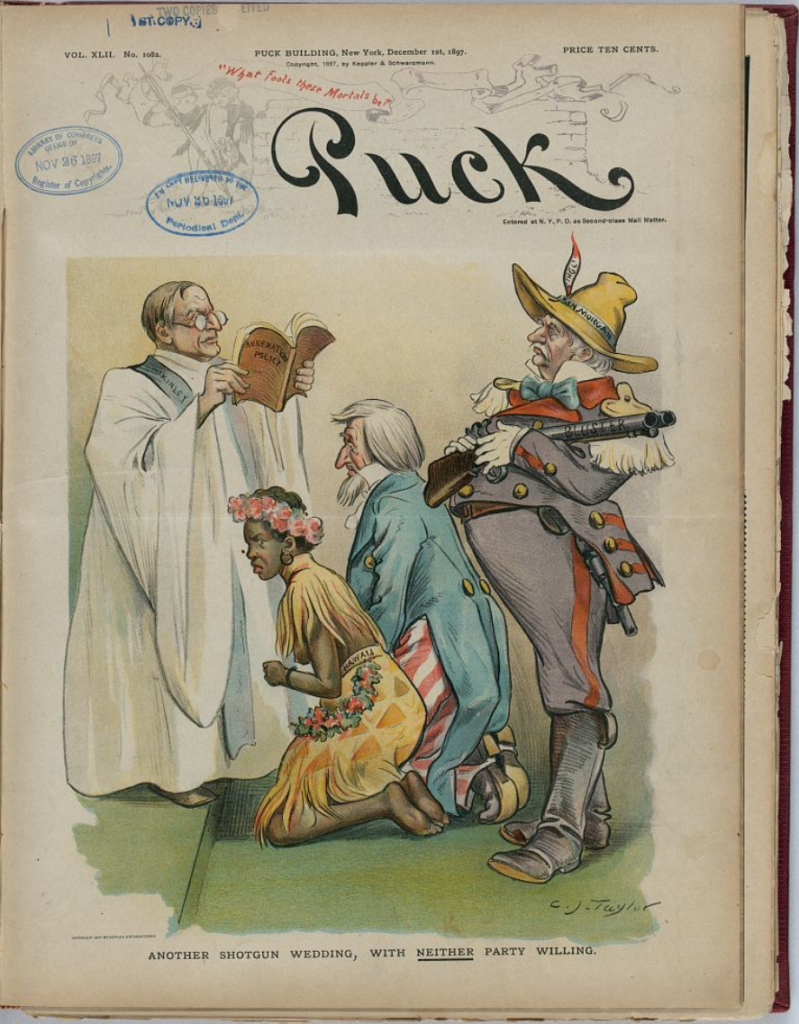

Another Shotgun Wedding, With Neither Party Willing

Charles Jay Taylor, 1897, for Puck Magazine, New York, New York

This cartoon depicts a shotgun wedding between Uncle Sam and a young woman labeled “Hawaii.” A cartoon of former Confederate general, Ku Klux Klan leader, and US senator John Tyler Morgan forces the marriage with a shotgun. Morgan was an ardent expansionist who was also a major proponent of Jim Crow laws, racial segregation, and the annexation of Hawaii. Then-president William McKinley sanctifies the marriage without a Bible, but rather a book entitled “Annexation Policy.”

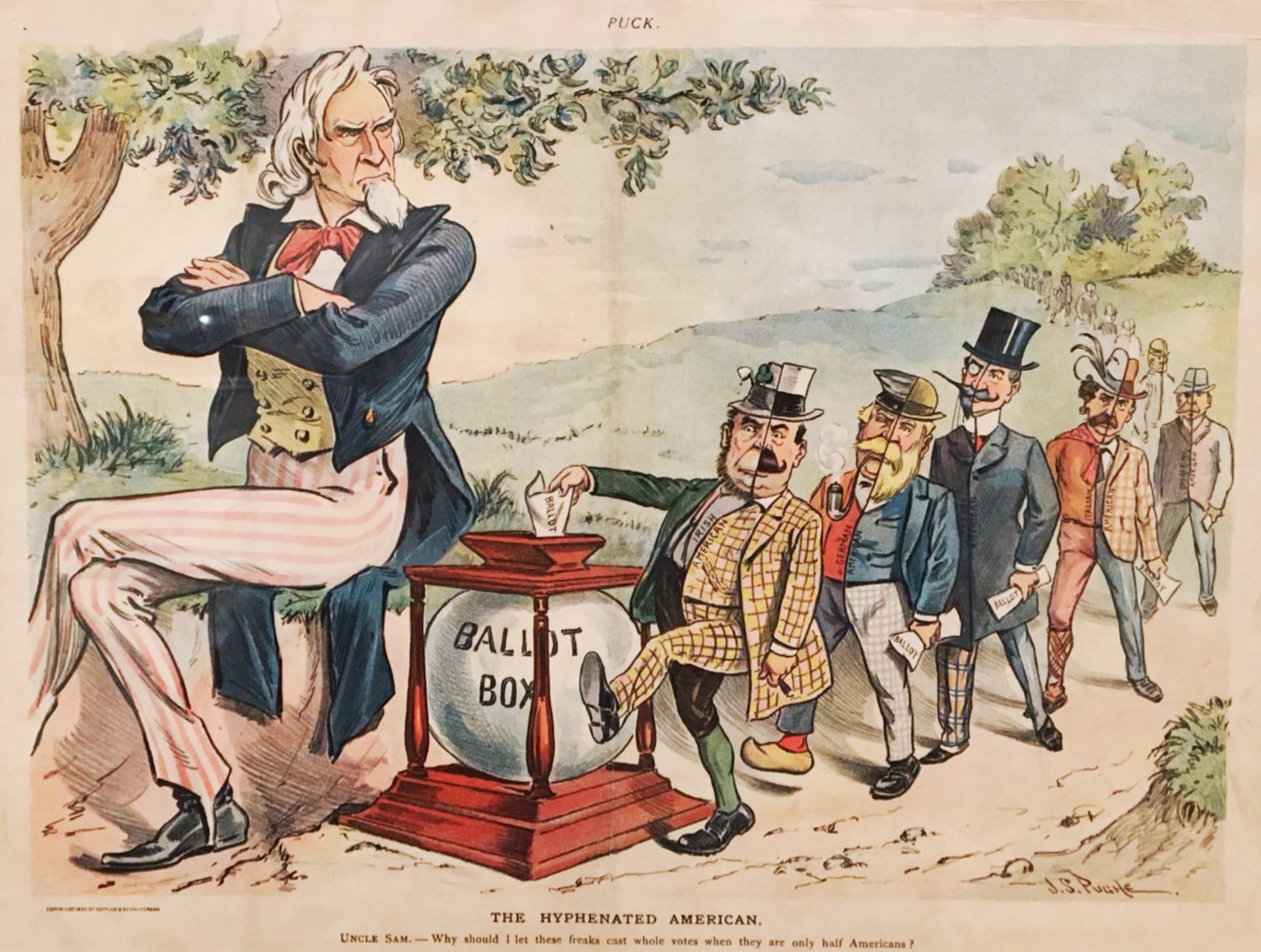

The Hyphenated American

J.S. Pughe, 1899, for Puck Magazine, New York, New York

This anti-immigrant cartoon questions the wisdom of letting so-called “hyphenated Americans,” or those that use a hyphen between their original ethnicity and their newfound citizenship (i.e. Irish-Americans, Italian-Americans, etc.), vote. Many people, including Theodore Roosevelt, demanded “100% Americanism,” and were skeptical of the loyalty of “hyphenated Americans.”