Regulating “sticks and stones” … and free speech on social media

Guest blog post by Gene Policinski

Remember the old children’s adage: “Sticks and stones can break my bones, but words will never hurt me?”

A retort to hurtful insults and harsh words that the young can sometimes hurl, the saying has picked up new impact – and irony in free speech terms – in the age of pervasive social media.

Retooled for these times, it could read “Sticks and stones do hurt my bones, and tweets encourage some to hurt me.”

Hate crimes against Asian Americans have spiked across the United States, totaling nearly 3,800 hate-related incidents across all 50 states, according to a report Tuesday by Stop AAPI Hate (Stop Asian American Pacific Islander Hate).

Demonstrators rally against anti-Asian violence in Los Angeles on March 13. Photograph: Ringo Chiu/AFP/Getty Images

Critics say crass remarks describing the COVID-19 pandemic as “Kung Flu” or the “China virus” and unproven claims about the origin of the pandemic have fueled those increased attacks. Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) has called on congressional colleagues “who have used that kind of hateful rhetoric — cut it out because you also have blood on your hands.”

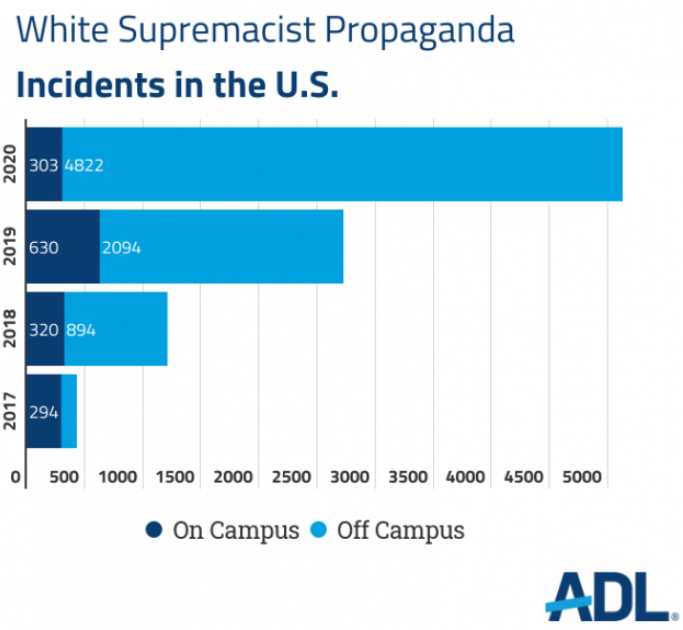

White supremacist propaganda reached new levels across the U.S. in 2020, according to a new report by the Anti-Defamation League on Wednesday, The Associated Press reported. It said 5,125 cases of racist, anti-Semitic, anti-LGBTQ and other hateful messages were spread through physical flyers, stickers, banners and posters — nearly double those noted in the 2019 report. The ADL said online instances probably totaled millions.

Increase in white supremacist propaganda incidents on and off-campus in the U.S. Source: ADL

Mass shooting at spas in the Atlanta area. Source: WSJ

Tuesday’s mass shootings at several Atlanta-area spas in which eight people, at least four of Korean ancestry, were killed may or may not be classified as a hate crime. Police said the suspected gunman told them he has a “sex addiction.”

Regardless, the incident already has raised renewed calls for government intervention to censor posts on social media sites that might be classified as “hate speech” – from clearly racist language to images and words that prolong decades-old demeaning stereotypes. The sites currently are protected by their own free speech rights and an added layer of legal security that prevents them from being held liable for content posted on their operations.

There’s no denying the value to society of stifling hate and ridding us of racial and ethnic profiling rooted in shameful history. But the government has proven to be very clumsy and very slow as a censor.

“Community standards” on obscenity have been difficult to define let alone fairly impose. The so-called “Fairness Doctrine” applying to broadcast TV and radio eventually failed because it produced the unintended consequence of chilling the open exchange of conflicting ideas. When TV or radio personalities have uttered racially insensitive remarks, the “court of public opinion” reacted within days while a court of law properly took months or years to work through due process.

And, as Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in a 2011 decision involving a group that protested at military funerals, “as a nation we have chosen a different course – to protect even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate.” Roberts also noted such a commitment is to be upheld even recognizing “speech is powerful. It can stir people to action, move them to tears of both joy and sorrow, and – as it did here – inflict great pain.”

Still, the speed, reach and very nature of social media seems to present a new challenge to the old idea that “the antidote to speech you don’t like is more speech” in opposition. Does hateful speech on social media create, in effect, a virtual community in which such language and imagery is not just acceptable, but with the impact of repeated echoing, has such resonance that some will be driven to action?

The quickest solution is for Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and such to act themselves to stifle dangerous posts. But do we want secret algorithms and private panels as the sole determiners of what is dangerous, and the proper remedy of what it or they deem improper speech.

Conservative commentators decry “Cancel Culture” and attack social media outlets for what they say is unfair treatment limiting conservative voices – even when such restrictions are applied to such things as clear misinformation about the effects of COVID-19 vaccinations. Liberal voices want bans on right-wing posts as racist and advancing white supremacist ideas, failing to recognize what Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson noted in the late 1940s: We sometimes need to hear ideas we find repugnant if only to be better armed to refute them.

There are other good reasons to wish the 24/7 omnipresence of social media could be restrained: So-called “revenge porn,” instances in which family members must endure over and over reposted public images or videos of loved ones insulted, assaulted, or killed. And then there are the kinds of societal dangers noted in a just-declassified report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), which found evidence that Russia and Iran both attempted through online tactics to influence public opinion during the 2020 presidential election.

What to do? Some solutions are relatively benign and hold great promise. Fostering competition in the social media sphere – either by funding startups or use of anti-trust laws – will reduce the power and impact of a few dominant Big Tech firms. Some social media companies already have taken steps to eliminate the financial rewards for posting blatant misinformation designed to produce as many “clicks” as possible.

Public pressure, even if it’s after-the-fact, also produced results more quickly than would moves by government regulators – and can serve as an instant barometer of public opinion. Racially-rooted jokes largely are absent in open society today not because a law was passed, but because the jokester finds quick disapproval – and for some, commercial, social or political consequences.

We have found ways in laws openly arrived at and tested openly in the courts to prevent – or at least punish – speech deemed harmful. We can file lawsuits over defamatory remarks and the authorities can prosecute conduct spurred by “fighting words” that are outside First Amendment protection.

There are ways to draw the fine First Amendment lines between repugnant ideas and illegal conduct: The Supreme Court has ruled that cross-burning can serve as an emblem of racist views and thus be protected speech but becomes criminal conduct when the intent is to intimidate a person or group.

Hard to make such decisions, create such laws or draw such lines? Yes. Likely to be stop-start, one-step-forward-at-a-time path to a workable system? Again yes. Likely to fall short at times and be frustratingly slow even in success? Almost assuredly. And in the end will we need to simply take personal responsibility to question what we read, hear and see? Absolutely.

It will take that kind of creative approach, deep engagement, constant vigilance and frequent revision and revisiting if we wish to stop short of some kind of proposed instant cure like a national speech czar – an impossible job, but with the real power of the government to rule for a time over what we say or post.

Gene Policinski is a trustee of the First Amendment Museum and a First Amendment scholar. He can be reached at genepolicinski@gmail.com.

Related Content

Watch our One on 1 interview with Gene Policinski.

Check out the rest of our One on 1 series: short, in-depth interviews reveal how Americans practice and value their First Amendment freedoms, and will encourage you to do the same.