For those looking to disrupt, to make good trouble, or to create social change, remember this important principle: movement creates friction. And, perhaps no civil liberty creates more friction than freedom of speech.

It isn’t easy to present unconventional ideas when the world stubbornly prefers the status quo. Being a catalyst means you will upset someone’s norms. Even someone who shares the same values as you might disagree with your tactics. But here’s a universal law that is shared in the world of science, art, and activism: friction isn’t always a bad thing.

Friction can be a useful force to slow you down so that you exercise more caution. Whether you are slipping on ice or self-conceit, an opposing force can prevent a fall.

Friction can also be used to generate heat and electricity. You can get warmth if you rub your hands together quickly, in the same way that rough opposition can ignite support in important ways.

Friction can also be used to test the strength of something. In the same vein, it is through challenge that the resolve and effectiveness of your ideas will be forged.

Of course, friction isn’t always pleasant. But as a famous African proverb states, “Smooth seas do not make skillful sailors.”

Freedom of expression sometimes creates friction with other people, but it almost certainly guarantees that friction is present when it comes to challenging the government. And it is in the best interest of the government, as it is in the people whom it serves, to do everything possible to protect that right. After all, dissent is patriotic. And when it comes to protecting our liberties, it is important to distinguish the difference between what we need and what we like. We like to hear things that we already agree with—but we need to be able to engage in civil discourse without worrying about backlash from the government.

It’s often unfortunate that debates around the First Amendment are often framed in the most extreme of circumstances: the speech of political candidates, how people perceive the reach of social media, the display of confederate flags on state property, and so on. However, when political issues cater to and are framed by the outer edges, the deepest impact is felt by the middle. While people may fall across the spectrum, there’s a general consensus that racism and hateful ideas shouldn’t be tolerated, so it’s less of a conflict of values and more of a disagreement on the possible solutions. However, my own story is a cautionary tale against trading in civil liberties in exchange for comfort or convenience.

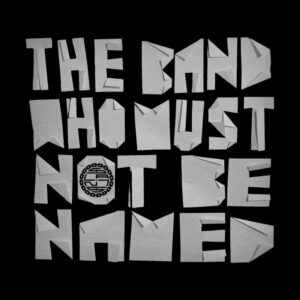

For years, I was engaged in a deep fight for the right to register the trademark for my Asian American band, The Slants. But therein lies the problem: The Trademark Office believed that our ethnicity provided the context to turn an ordinarily neutral word, “slant,” into a racial slur. Evidently, someone in the government didn’t like our use of the term. Neither our intention to reappropriate it nor our community’s support for it mattered—so much so that they dismissed any legitimate evidence that disagreed with their decision.

The government’s conviction on this was strong enough to justify suppressing the protected speech of multiple traditionally marginalized communities. They allowed the Trademark Office to use false claims in their legal brief without accountability. They were even allowed to justify the use of my racial and ethnic identity as the primary reason for connecting us with a racial slur. All because the government didn’t like what we had to say. We were creating too much friction.

The stubborn pushback from the Trademark Office wasn’t all that surprising – government offices often have the incentive to maintain the status quo, to reduce friction, so to speak. Eventually, that case landed before the United States Supreme Court, where we won unanimously because of the First Amendment. While the case eventually ended in victory, it took eight years of my life and cost countless resources—years I’ll never get back. No one should ever have to go through something like that – but that’s what happens when the power of the censor rests in the hands of the government.

We shouldn’t let the fear of the uncomfortable, such as someone using speech you disagree with, justify the suppression of rights for others—especially when the power to silence comes from the government. We have other options to show our distaste for ideas: to protest, to debate in the marketplace of ideas, and to vote with our dollars in the marketplace of economic exchange. These options are essential for democracy.

True equity isn’t achieved by sweeping government actions that negatively affect some communities more than others. The restriction of speech disproportionately hurts the marginalized and the powerless. There is power in allowing civil discourse to take place, as it is the primary means for overcoming fascism and oppression.

We should not discourage people from using wit, irony, or reappropriation to disarm the malicious. Unfortunately, the debate on free speech has almost always focused on those who abuse it. We know that the cost of free speech sometimes means having disagreeable speech. But the price that is paid for censorship is carried on the backs of the underprivileged.

An example of this is artistic expression, something that has continuously been understood as deserving the highest forms of protection under the First Amendment. Over the past few decades, prosecutors have been using violent, crime-laden lyrics of amateur rappers as confessions to crimes, threats of violence, evidence of gang affiliation, or revelations of criminal motive- and many judges and juries have gone along with it. The same approach has not been adopted with murder ballads (a popular form of country music), other genres of music, or other forms of artistic expression. It’s a perfect example of Orwell’s satire in play: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

We often take civil liberties and our First Amendment freedoms for granted, but they aren’t protected as they should be. A guarantee on paper is only as good as the people willing to ensure that those freedoms are made real. We need persistent awareness and troublemakers willing to fight these battles for other people to ensure our rights are available.

So as you create movement in your life, ask what you can do with your friction: Do you need to check your ego, heat things up, or test the strength of your resolve? Once you understand the kind of internal opposition that you’re facing, you’ll have better external options for moving forward. And, if you’re creating a movement for your community, ask yourself: are you the friction? How can you use and create more resistance to bring more justice for all?

By Simon Tam

Simon Tam is an author, musician, and activist. He is best known as the founder and bassist of the first all-Asian American rock band, The Slants. He helped expand civil liberties for minorities by winning a unanimous victory at the Supreme Court of the United States for a landmark case, Matal v. Tam, in 2017. He also leads The Slants Foundation, a nonprofit that supports arts and activism projects for underrepresented communities. In 2019, he published his memoir, Slanted: How an Asian American Troublemaker Took on the Supreme Court, which was named “One of the Best Books on the Constitution of All Time” by BookAuthority and won an award for Best Autobiography/Memoir from the Independent Publisher Book Awards.