Guest blog post by Gene Policinski

The words “banned” and “books” ought never be necessary in the same sentence.

Even when used in the benign way of “Banned Books Week,” an annual event that this year runs from Sept. 26 to Oct. 2. Come to think of it, even that yearly title should not be in our vocabulary.

Much better to have just “Books Week,” don’t you think? Better sound to it, and a better idea behind it – except that we still will face the affront to the First Amendment’s concept of a “marketplace of ideas” from those who would hide from facts rather than face up to them.

Opposition is vocal today – and sometimes menacing – to the exposure to ideas some would not see: Too negative, too hateful, too shocking, too offensive, or just too critical of our past or our present. Those voices who would silence authors, and in doing so blind readers, declare multiple justifications: Patriotism, morality – as they see it – and even safety.

If only the issue of banning books was a subject unto itself. But in 2021 it’s not. Banning books in a local library or school system comes amid a time when “cancel culture” is on the rise, from electronic shunning via social media of people for supposed transgressions of the strict application of “political correctness” to physical intimidation at school board and town hall meetings with claims of “protecting the children” from issues that, in reality and in all too short a time, they will have to confront as adults.

Silence the speaker, the author, the social influencer and “poof,” problem solved – so the theory goes if advocates from both the left and right were to be honest with themselves. But taking a shortcut through the First Amendment by banning books – and the discussions and disruptions that come with reading them – is much quicker than dealing frankly and effectively with challenges such as the legacy of racism and prevalence of hate, with the debilitating effects of long-term poverty and the corrupting decay of discrimination.

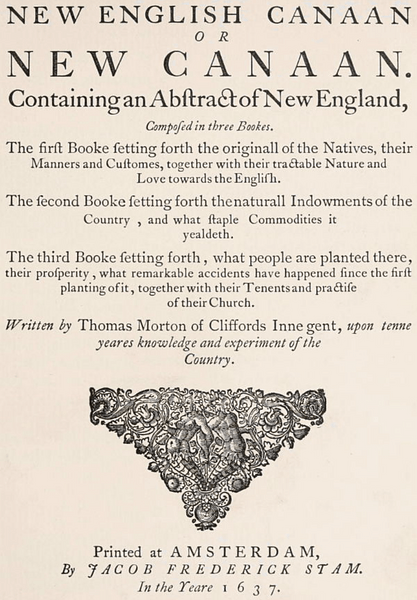

This instinct to censor that which upsets us is not new. In what is believed to be the first ban on a book in what would become the United States, Puritan officials in Massachusetts banned a “tell-all” book critical of their new colony’s practices, “New English Canaan” – which contained serious criticisms that the Puritan ethic would lead to a nation little more than a “Christian labor camp”. The book also ridiculed the Puritan’s lack of learning, their gloomy approach to life, and even called Myles Standish and his men “Captain Shrimp and the nine worthies.” Pretty heady stuff for the middle-1600s, we can assume.

The issue of banning books was debated some 40 years ago on a higher plain, in the U.S. Supreme Court, in Island Trees School District (New York state) v. Pico – with a fractured court voting in 1982 to void a decision by the local school board to ban books by several notable authors.

The controversy and the decision covered ground all too familiar today. School board members, after attending a meeting sponsored by a conservative parents’ groups, banned nine books they found were available in high school and middle school libraries, as “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Sem[i]tic, and just plain filthy.” The board later told a district court that “[i]t is our duty, our moral obligation, to protect the children in our schools from this moral danger as surely as from physical and medical dangers” – even after a committee created by the board advised reinstating the books with appropriate age and curriculum conditions.

“Pico” is notable as the first time the Supreme Court ruled against banning books from libraries, though the decision acknowledged school board authority over classroom materials. Perhaps the greatest point of agreement among the justices was that no one has the power to ban a book because of its content – be that political view, sexual imagery, or controversial subject. And, as one justice wrote in a concurring opinion, the First Amendment protects not only the right to express ideas, but also the right to receive them.

To be sure, no court decision requires anyone to read a book or prevents anyone from criticizing its use in schools – or it’s very value. But, as Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson wrote in the 1940s, we ought to be exposed to ideas we find even repellent and repugnant, if only to be better prepared to argue against them.

The American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom reported for this year’s Banned Books Week there were 156 challenges in 2020 to library, school, and university materials and services in 2020, with 273 books targeted. [Top 10 Most Challenged Books Lists | Advocacy, Legislation & Issues (ala.org)].

Most often cited by opponents: Accounts of LGBTQIA lives, a focus on racial discrimination, profanity, depictions of alcoholism or “anti-police” views. Among those most challenged: “Of Mice and Men,” by John Steinbeck; and “To Kill a Mockingbird,” by Harper Lee – to my view, certainly literary classics, but hardly the cutting edge of a rampant modern-day agenda to brainwash unsuspecting citizens.

Banning a book – or a thought – has never solved any problem or corrected any ill. But reading a book that leads to a thought has.

Gene Policinski is a member of the board of trustees and board secretary of the First Amendment Museum and frequently writes on issues involving the First Amendment.

Related

Banned Books Week 2021: Young Adult Books

We consider seven examples of young adult books that have been banned throughout the United States, starting with the Twilight series. Read more.

Banned Books One on 1

Join Maine author Spencer Stephens as he talks to us about censorship, banning books, and how to use your First Amendment rights every day.