Do you have what it takes to be an American Citizen? Take the practice test now to find out.

Category: News

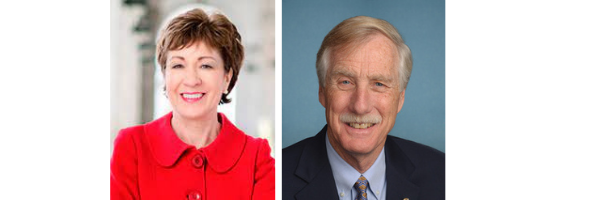

Senators Angus King (I-Maine) and Susan Collins (R-Maine) share their thoughts on the importance of the First Amendment in advancing democracy.

“[The First Amendment] enabled us to remain a free people, it enables us to engage in the rigorous debate that we have in this country, and to communicate with one another freely.”

– Senator Angus King

“Freedom of expression is the cornerstone of all other freedoms.”

– Senator Susan Collins

Celebrate the 230th Anniversary of the Ratification of the Bill of Rights on December 15th

The five essential freedoms that empower the people to actively engage in the democratic process were not enumerated in the original Constitution drafted at the Philadelphia Convention of 1787, but were added in 1791 when the Bill of Rights was ratified. Those five freedoms—religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition—are safeguarded and preserved in the First Amendment to the Constitution. In honor of the 230th anniversary of the ratification of the Bill of Rights, the First Amendment Museum hosts a virtual celebration on this historic day. Listen to the remarks of U.S. Senators, historians, lawyers, journalists, and advocates on the importance of the First Amendment in advancing democracy.

A Double-Edged Sword: Reflections on 230 Years of First Amendment History

Left to right: Speakers Dmitry Bam, Annette Gordon-Reed, and Peter Onuf

The First Amendment gives voice to those who might otherwise go unheard and empowers Americans to create change in our society and government. It can also be used to prevent change from happening, to silence minorities, and to keep privilege in position. Each action is seen by some part of the population as an effort to create a more perfect union. On the 230th anniversary of the ratification of the Bill of Rights, join FAM Board member Peter Onuf, celebrated law professor and historian Annette Gordon-Reed, and noted Constitutional law professor Dmitry Bam as they reflect on the ways we have used the First Amendment as a tool to both transform society and to secure the status quo.

Watch & Learn:

Importance of the First Amendment: Remarks by U.S. Senators from Maine

Left to right: U.S. Senators Susan Collins (R-Maine) and Angus King (I-Maine)

The First Amendment Museum shares remarks from U.S. Senators Susan Collins (R-Maine) and Angus King (I-Maine) on the First Amendment’s importance in advancing democracy.

U.S. Senator Susan Collins (R-Maine)

U.S. Senator Angus King (I-Maine)

Watch & Learn:

Our Freedoms at Work

Left to right: Jennifer Rooks, Chelsea Miller, and Destie Hohman Sprague

The First Amendment impacts the work of journalists, activists and lobbyists every day. Watch Maine Public’s Public Affairs Host and Producer of “Maine Calling” Jennifer Rooks, CEO and Co-founder of the Freedom March NYC Chelsea Miller, and Executive Director of the Maine Women’s Lobby Destie Hohman Sprague reflect on this moment.

Guest blog post by Gene Policinski

Let’s begin by acknowledging that many of you reading this don’t like or respect journalists – or at least don’t trust what you see and hear from many of them.

The new Freedom Forum survey “Where America Stands” about the First Amendment found that we’re ambivalent about the free press we have even as we support press freedom as an important value.

In the survey, 58% of Americans agreed the news media should act as a watchdog on government. But only 14% of respondents trust journalists.

But Friday morning the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to journalists Maria Ressa of the Philippines and Dmitry Muratov of Russia – and that announcement should be cheered no matter where you fall in those survey results.

“Free, independent and fact-based journalism serves to protect against abuse of power, lies, and war propaganda,” the Nobel committee chairperson said in announcing the recipients. The pair won this year’s prize “for their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace.”

Both journalists face death threats. Ressa co-founded the online news web report Rappler in 2012, focused on reporting on Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte’s controversial anti-drug campaign – which has been linked to human rights abuses including murder – and on government attempts to spread misinformation for political purposes.

Muratov was one of the founders of the independent Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta in 1993, and editor-in-chief since 1995. The newspaper is one of the few national news operations still open in Russia, often reporting on President Vladimir Putin’s ties to corruption and killings. Six of the paper’s journalists have been murdered, including investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya, who was shot in 2006 in the elevator of her Moscow apartment building – on Putin’s birthday.

The Committee to Protect Journalists reports that 18 journalists have been killed thus far in 2021.

Lest we think threats to the working press are just an overseas issue, the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker – a collaborative organization of free press groups – lists 134 assaults on reporters and correspondents this year – ranging from physical attacks, to injuries from police “soft bullets,” to online harassment – and 34 incidents in which equipment was deliberately damaged. Recent assaults have come when reporters were covering anti-COVID-19-mask demonstrations.

The last journalists killed in the U.S. in connection with their work was in 2018, when a gunman killed four newsroom staffers and a sales associate at the Capitol Gazette, in Annapolis, Md.

The skepticism showing in the Freedom Forum survey is disappointing given the nation’s long commitment to freedom of the press – along with the four other First Amendment freedoms of religion, speech, assembly, and petition. But we live in difficult, polarized times in which a combination of financial weakness, technological challenges, and political opportunism have fed increased attacks on journalism as biased and untruthful.

Once seen as a global beacon of press freedom because of strong First Amendment protections, politicians in recent years have profited from portraying “the media” as – in one infamous claim by ex-President Donald Trump – “enemies of the people.”

Perhaps even more damaging to public perception has been the massive layoffs of reporting staffers and newspaper closings around the nation. In the past 20 years, newsroom staffing has fallen by more than one-half, and so many news outlets have closed that large areas of the U.S. are now considered “news deserts” in which no local newspaper or broadcast operation exists.

And then there are the high profile, pseudo-journalism attractions on cable news networks, with programs and high-rated performers offering opinion-laced commentary under the guise of “news” – all amplified by social media targeted by algorithms to those already inclined to be media critics.

To be sure, no media operation is perfect. But increased efforts by the news industry to include diverse views and to reach minority audiences all too often ignored in the past, have yet to show any major impact on the public’s views. At least two recent studies show even the news media’s traditional role as a “watchdog on government” has less support from the public than in years past.

Bluntly, even if you don’t like most of what the news media in the U.S. does right now, you’re wrong to abandon support for the “watchdog” role. Most public officials are honest, hard-working people who should be applauded for their work on our behalf. But some are not. Mistakes also occur. And it’s asking too much, in a common-sense way, for public bodies and elected officials to police themselves while doing their jobs.

There’s a reason Putin and Duterte – and dozens of actual and would-be despots around the world – fear and attack journalists: As the old saying goes, “sunlight is the best disinfectant.”

At its best, and often, journalism provides us with that “sunlight” – information that reports, reveals, and tracks down those who must be held accountable as they control the public purse strings – and at times, our liberty, and lives.

Ressa has been arrested many times, and is the target of an online hate campaign because of her reporting on the Duterte regime. Muratov said of the Nobel honor that it belongs to “those who died defending the right of people to freedom of speech.”

In a program Friday at the annual News Leaders Association convention, CPJ executive director Joel Simon noted that governments worldwide have “deployed their resources” in support of a “hate machine” to manipulate public opinion against journalists. Simon and Brazilian journalist Patricia Campos Mello – who also faces death threats — noted that threats to a free press in the U.S. are more like to resemble those in her nation: legal moves to obstruct truthful reporting and organized efforts at misinformation to cast doubt about the role of journalist watchdogs.

Skepticism about the news media no doubt will not see a major shift because of the Nobel committee’s decision. And legitimate criticism of the news media has value.

But perhaps we all might pause for just a moment to honor the courage shown by Ressa, Muratov, Campos Mello, and thousands of others who risk their safety and their lives to bring the news to their fellow citizens, here and abroad.

Gene Policinski is the secretary of the Board of Directors of the First Amendment Museum and frequently writes on issues involving the First Amendment.

Related

Blogpost: China shuts Hong Kong’s Apple Daily newspaper – and assaults freedom

The newspaper Apple Daily, a fixture and voice for democracy in Hong Kong for decades, closed days after China arrested its owner and its top editors and froze its financial assets. Keep reading.

Blogpost: Journalists again in the crosshairs in Gaza Strip violence

Who’s on the “right side” in the outbreak of violence between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip? Well, don’t look for that answer here – but do know that good journalism allowed to do its job is among the ways to explore that question and more. Keep reading.

We are hosting a free Open House on July 4 from 1 – 5 pm that will include family-friendly crafts, games, tours, and food.

We are right along the parade route for the Augusta Parade – so come, have fun, and get your spot for the parade!

All are welcome – come celebrate the Fourth of July with the First Amendment Museum!

Apple Daily was a pro-democracy newspaper

Guest blog post by Gene Policinski

The newspaper Apple Daily, a fixture and voice for democracy in Hong Kong for decades, closes this Saturday, days after China arrested its owner and its top editors and froze its financial assets.

Source: BBC

The fate of one newspaper, halfway around the world, may not have grabbed your attention before. But the shutdown is worthy of some thought by us all, as a significant marker in the effort by Beijing to extinguish this beacon of democracy in the world’s most populous nation.

Apple Daily founder Jimmy Lai was jailed some months ago on phony charges regarding a real estate lease, and Lai and op editors and news executives of Apple Daily now face vague charges related to “national security” – with life sentences a possibility.

The final move to silence Lai and his newspaper, frequent critics of the anti-democratic policies of the mainland government, was to freeze more than $2 million in assets of companies connected to the Hong Kong newspaper – rendering it unable to pay staff or bills.

Jimmy Lai, Source: Getty Images

In 1997, when Great Britain ended its colonial control of the city, Chinese leaders promised Hong Kong residents that they would continue to have what we in the United States would call First Amendment freedoms for at least 50 years.

Source: HKFP

No more. Hundreds of arrests, police brutality toward pro-freedom protesters and severe financial moves like those against Apple Daily are proof that China no longer honors that promise – or respects democracy.

Lai is a self-made millionaire and publisher who choose to remain in Hong Kong to be a vocal critic of China’s repressive moves. As a close associate told me some weeks ago, “he has homes around the world. He chose to stay and to speak out. He knew the risks.”

Lai has been honored for his courage and voice by First Amendment groups like the Freedom Forum, who awarded him its 2021 Free Expression Award last April – just one day before he was found guilty of supporting “illegal assemblies.” And yesterday in Paris, the press freedom group Reporters Without Borders staged a mock funeral, complete with casket, outside the Chinese embassy to denounce the forced closing of Apple Daily.

While the jailings and closings are worthy of concern on their own, we also need to recognize that despotic regimes world-wide are watching the international response to China’s action. Protest may not free Jimmy Lai and his colleagues or bring back Apple Daily. But silence in the face of repression will speak loudly to those who aim to quiet dissent anywhere in the world – including the U.S.

Source: RSJ

In our own nation, a free press needs support for multiple reasons – financial stress as advertising mainly has moved from broadcast and print outlets to social media and other online operations; a loss of confidence from sizeable portions of the public; and aggressive moves by politicians who would like nothing more than eliminate the “watchdog on government” that might hold them accountable to voters.

A public stand for Apply Daily and Jimmy Lai could help in Hong Kong – and will be a vocal show of support for basic freedoms of conscience and free speech worldwide. Anyone who advocates for First Amendment freedoms as a cornerstone of democracy, here and elsewhere, should make that support known however they can.

Memo to China: Unfreeze Apple Daily’s assets and stop arresting and harassing its staff. Abide by your promises of freedom for the citizens of Hong Kong. Release Jimmy Lai.

Gene Policinski is a member of the board of trustees and board secretary of the First Amendment Museum and frequently writes on issues involving the First Amendment.

Supreme Court rules for student in social media free speech case Mahanoy Area School District v. BL

Guest blog post by Gene Policinski

Public school students can speak freely – even vulgarly – off-campus in most instances without fear of being punished by their schools, an 8-1 majority of the U.S. Supreme Court said Wednesday in a case that had a lot of First Amendment advocates holding their breath.

The Tinker siblings from Tinker v. Des Moines

Most notably, Mahanoy Area School District v. BL, the court Wednesday upheld the main principle of the core 1969 student speech case, Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, that neither students nor teachers “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

There was wide concern that a new conservative majority on the court – which over the past 40 years has supported school authority to regulate some in-school student speech – would extend the power of administrators into after-school hours and off-school grounds.

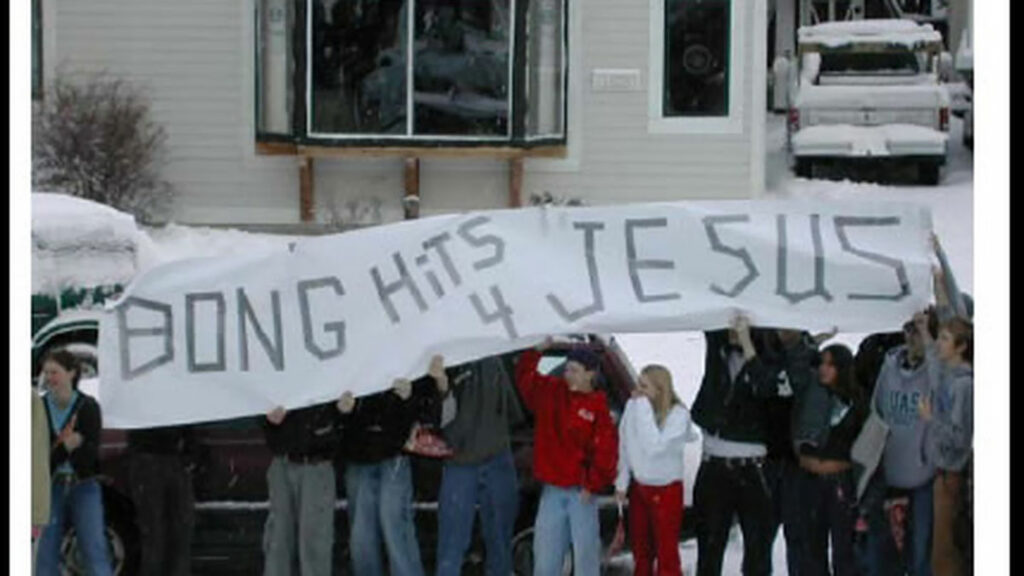

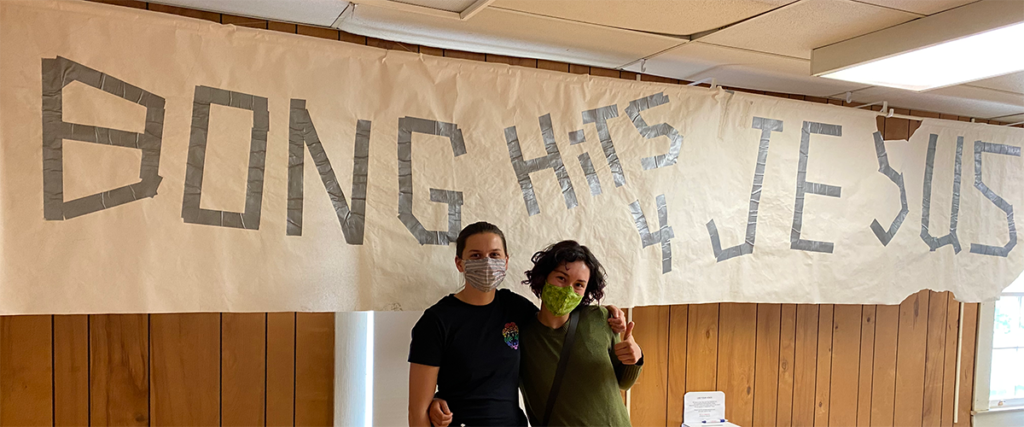

In one of the more recent cases, Morse v. Frederick – more popularly known as the “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” case – the court upheld an Alaskan school’s right to punish a student for the off-campus banner carrying those words, as an important school role in preventing use of illegal drugs. [NOTE: The “Bong Hits” banner is currently on display at the First Amendment Museum, in Augusta, Maine).

The ruling restrains the off-campus reach of school officials, even as its decision acknowledges exceptions such as field trips, athletic events, bullying that continues off-campus or when student speech specifically targets an individual teacher or student. The decision also notes the increasingly difficult line to draw between “on” and “off” campus given the rising use of online instruction and social media in general.

Brandi Levy, the student in question. Source: ACLU

In the case at hand, a student used and posted on social media criticisms of the school and its cheerleading squad when she failed to make the varsity team. On the following weekend, while at a local convenience store, she used her smartphone to post two images on Snapchat – where such images disappear after a time — one showing her and friend with raised middle fingers and repeated use of the f-word. A few other students relayed the images around the school and to teachers and coaches, and the posts were discussed briefly during an Algebra class taught by one coach.

The court said with no evidence of significant disruption of the educational work of the school, legal justification was lost for a public school to punish the student for her posts – noting such territory has been reserved to parents. Also, the court said that since school officials already can regulate in-school student speech that otherwise would be protected, extending that authority to off-school hours “may mean the student cannot engage in that kind of speech at all.”

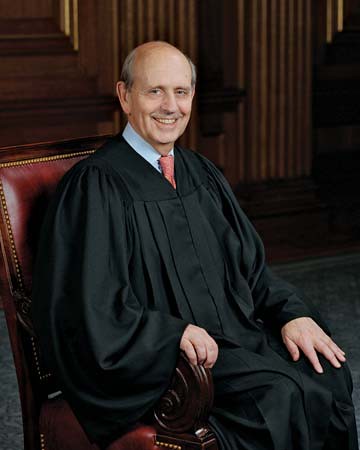

Justice Stephen J. Breyer, writing for the majority, left open the door for adding circumstances in which school might be able to act without violating First Amendment rights: “Particularly given the advent of computer-based learning, we hesitate to determine precisely which of many school-related off-campus activities” might warrant future oversight and “neither do we know how such a list might vary, depending on a student’s age, the nature of the school’s off-campus activity or the impact on the school itself.”

In words that will echo longer after the specifics of this case, Breyer took special note of the role of schools as “the nurseries of democracy.” The governing system only works, he said, if it protects “the marketplace of ideas” in which “free exchange facilitates an informed public opinion.”

Breyer said that “Schools have a strong interest in ensuring that future generations understand the workings in practice of the well-known aphorism, ‘I disapprove of what you say but I will defend to the death your right to say it’.”

Justice Stephen J. Breyer

Justice Clarence Thomas the lone dissenter, offered the view that schools are unlike other public bodies in that they traditionally have functioned in the place of parents – and thus are not bound in the same way by First Amendment concerns. He also wrote that the intent of the cheerleader’s post was to “degrade” the program and cheerleader staff in front of other students, “subverting” the coaches’ authority.

The fact that schools in some circumstances may act as parents does not, to me, mean that applies in all cases – especially when students are away from school, after regular school hours and not participating in a circumstance that would imply school approval or involvement. And the majority opinion by Beyer notes that the coaches saw no impact on their work other than having to respond to a few students when the posts became public.

While not dismissing the vulgarity of the student’s remarks, Breyer noted that had she “uttered the same kind of pure speech … the First Amendment would provide strong protection” as it does for “even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure we do not stifle public debate.”

As if to speak to the media attention that – at times, somewhat gleefully in my view – focused on the shock value of a cheerleader using the “f-word” in the posts, Breyer said “it might be tempting to dismiss (her) words as unworthy of the robust First Amendment protections discussed herein. But sometimes it is necessary to protect the superfluous to protect the necessary.”

The “necessary” here was the need to balance the need for schools to be able to educate, the right of parents as the primary actor in overseeing their children’s conduct away from school and – most importantly – the need for student’s First Amendment rights to be respected and protected, both in the moment and as a learning tool for full participation in a self-governing democracy.

Gene Policinski is a member of the board of trustees and board secretary of the First Amendment Museum and frequently writes on issues involving the First Amendment.

Related Content

Learn more about the Morse v. Frederick case, in which the Supreme Court ruled against off-campus student free speech, and see the original banner that caused it all in our Bong Hits 4 Jesus exhibit.

On June 15th, 2021, the live Maine Public radio call-in show, Maine Calling, hosted our CEO Christian Cotz as a panelist on the episode “First Amendment: How The Constitutional Protection of Freedoms Applies To Issues Of Our Times.”

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution establishes the freedom of speech, religion, and assembly. But the Founding Fathers couldn’t have anticipated contemporary challenges such as social media, hate speech, religious extremism and public school funding. We’ll discuss how the First Amendment applies to current events. Plus, we’ll learn about Maine native and newspaper editor Elijah Lovejoy and Maine’s First Amendment museum.

Maine Calling episode description

Christian was joined by two other panelists: author Ken Ellingwood whose latest book is First to Fall: Elijah Lovejoy and the Fight for a Free Press in the Age of Slavery, and Hasan Jeffries, professor of history at the Ohio State University.

Listen to the recorded programming at the Maine Calling website.

Journalists again in the crosshairs in Gaza Strip violence

Guest blog post by Gene Policinski

Who’s on the “right side” in the current outbreak of violence between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip?

Well, don’t look for that answer here – but do know that good journalism allowed to do its job is among the ways to explore that question, and more.

Destroyed building in Gaza City. Source: MAHMUD HAMS/Getty Images

For the moment, here is what we do know, thanks to reporters and correspondents risking their lives among bombs and rockets.

We again see disturbing images of civilians in Israeli cities and settlements dashing for underground shelters against incoming rockets fired from Gaza. On the Palestinian side, again we see wailing women and weeping men, cradling injured children, or mourning over bodies of family members killed in airstrikes.

We may be seeing less, though, even as the two sides appear to be groping toward yet another tenuous cease-fire.

Even scrupulously neutral news operations such as The Associated Press have raised suspicions that Israel is working to control news reporting from the region. The New York Times reported “a prominent 12-story building in Gaza City …(was) destroyed in an Israeli airstrike” – a building that house AP offices as well as other news outlets.” Reporters and staff were warned of the attack only a short time before bombs fell.

An Israeli airstrike destroyed a building in Gaza City that housed media outlets, including The Associated Press and Al Jazeera. Source: New York Times

AP president Gary Pruitt said on Saturday, May 15 that “the world will know less about what is happening in Gaza because of what transpired today.” And that gets to the heart of the matter: We need information from independent news sources, with such reports all the more important and urgent as the death tolls rise.

Another circumstance also has produced complaints from multiple press operations: Early Friday, Israeli officials told international journalists – but not local Israel news outlets – that IDF forces had entered the Gaza Strip, only to pull back the statement about an hour later. Journalists are dependent on government announcements because Israel has declared its side of the Gaza region off-limits to news organizations.

A later report on the non-incursion in the Jerusalem Post was headlined “Did IDF deception lead to massive aerial assault on Hamas’ Metro?” – noting speculation that Israel’s initial claim was an effort to get Hamas’ fighters to gather to repel such an incursion, making themselves easier to target.

Members of the press in Gaza. Source: Newsweek

The independent Committee to Protect Journalists, headquartered in New York City, asked in a statement if the IDF was “deliberately targeting media facilities in order to disrupt coverage of the human suffering in Gaza.” On Wednesday, May 19, it also condemned the killing of a Palestinian journalist for a Hamas-run radio station, Al-Aqsa in an aerial attack on the top floors of a Gaza apartment building, saying “Israeli authorities must explain why they bombed the home of a journalist, a civilian who was protected under international law.”

Armed members of the Palestinian Hamas, Source: AFP

For Hamas’ part, Israeli officials said they believed the terror group was using the Gaza building to direct rocket attacks on the Jewish state. In response to criticism of the bombing, an Israeli official reminded reporters that “this week’s case is far from the first time Hamas used journalists as human shields. During the 2014 Gaza War, Hamas was caught red-handed launching rockets 50 yards from a Gaza hotel known to be housing foreign journalists.”

A government spokesman also said it appears to Israel that Hamas used the brief warning time to remove possible munitions from the building before the attack began. The IDF has not yet responded to media requests for evidence.

Reporting from the Middle East – and globally – is difficult enough without the added burden of being in the crosshairs of whatever combatant chooses to attack the press, an increasingly common tactic. With the introduction of the Web and social media, journalists are no longer needed to convey messages or images to the outside world – and thus “protected.” In fact, as both governments and terrorist organizations have developed sophisticated online operations, reporters often are viewed as threats to carefully crafted narratives.

The Middle East has long been a danger zone for journalists, from kidnappings and murder to the risks of reporting from live combat areas and in operating in nations controlled by dictatorial regimes. The nonpartisan group Reporters Without Borders’ recent World Press Freedom Index 2021, noted that given political tensions and the COVID-19 crisis … “most of the Middle East’s governments responded … with increased authoritarianism,” undermining already shaky free press guarantees across the region.

The decades-old Middle East crisis won’t be solved by journalists, and to be sure some – perhaps many – will report through the lens of nationalism or partisanship. But many also will report the facts needed to find an end to the conflict – if they can gather and report them without fear of restrictions, injury, or death.

Gene Policinski is a trustee of the First Amendment Museum and a First Amendment scholar. He can be reached at genepolicinski@gmail.com.

Related Content

Watch scenes of Americans using their First Amendment freedoms to voice their opinions regarding the recent outbreak of violence between Israel and Palestine.

Across the country, protests, marches, speeches, and gatherings have occurred – in support of both Israel and Palestine. View now.

Regulating “sticks and stones” … and free speech on social media

Guest blog post by Gene Policinski

Remember the old children’s adage: “Sticks and stones can break my bones, but words will never hurt me?”

A retort to hurtful insults and harsh words that the young can sometimes hurl, the saying has picked up new impact – and irony in free speech terms – in the age of pervasive social media.

Retooled for these times, it could read “Sticks and stones do hurt my bones, and tweets encourage some to hurt me.”

Hate crimes against Asian Americans have spiked across the United States, totaling nearly 3,800 hate-related incidents across all 50 states, according to a report Tuesday by Stop AAPI Hate (Stop Asian American Pacific Islander Hate).

Demonstrators rally against anti-Asian violence in Los Angeles on March 13. Photograph: Ringo Chiu/AFP/Getty Images

Critics say crass remarks describing the COVID-19 pandemic as “Kung Flu” or the “China virus” and unproven claims about the origin of the pandemic have fueled those increased attacks. Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) has called on congressional colleagues “who have used that kind of hateful rhetoric — cut it out because you also have blood on your hands.”

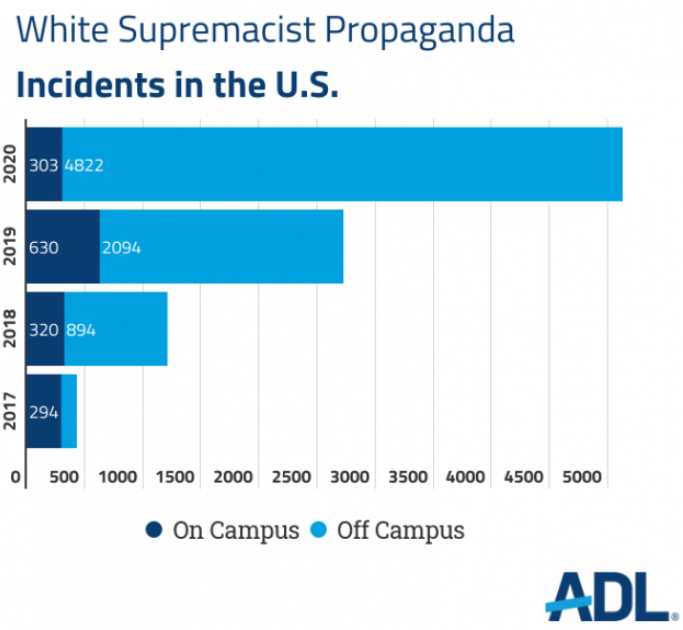

White supremacist propaganda reached new levels across the U.S. in 2020, according to a new report by the Anti-Defamation League on Wednesday, The Associated Press reported. It said 5,125 cases of racist, anti-Semitic, anti-LGBTQ and other hateful messages were spread through physical flyers, stickers, banners and posters — nearly double those noted in the 2019 report. The ADL said online instances probably totaled millions.

Increase in white supremacist propaganda incidents on and off-campus in the U.S. Source: ADL

Mass shooting at spas in the Atlanta area. Source: WSJ

Tuesday’s mass shootings at several Atlanta-area spas in which eight people, at least four of Korean ancestry, were killed may or may not be classified as a hate crime. Police said the suspected gunman told them he has a “sex addiction.”

Regardless, the incident already has raised renewed calls for government intervention to censor posts on social media sites that might be classified as “hate speech” – from clearly racist language to images and words that prolong decades-old demeaning stereotypes. The sites currently are protected by their own free speech rights and an added layer of legal security that prevents them from being held liable for content posted on their operations.

There’s no denying the value to society of stifling hate and ridding us of racial and ethnic profiling rooted in shameful history. But the government has proven to be very clumsy and very slow as a censor.

“Community standards” on obscenity have been difficult to define let alone fairly impose. The so-called “Fairness Doctrine” applying to broadcast TV and radio eventually failed because it produced the unintended consequence of chilling the open exchange of conflicting ideas. When TV or radio personalities have uttered racially insensitive remarks, the “court of public opinion” reacted within days while a court of law properly took months or years to work through due process.

And, as Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in a 2011 decision involving a group that protested at military funerals, “as a nation we have chosen a different course – to protect even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate.” Roberts also noted such a commitment is to be upheld even recognizing “speech is powerful. It can stir people to action, move them to tears of both joy and sorrow, and – as it did here – inflict great pain.”

Still, the speed, reach and very nature of social media seems to present a new challenge to the old idea that “the antidote to speech you don’t like is more speech” in opposition. Does hateful speech on social media create, in effect, a virtual community in which such language and imagery is not just acceptable, but with the impact of repeated echoing, has such resonance that some will be driven to action?

The quickest solution is for Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and such to act themselves to stifle dangerous posts. But do we want secret algorithms and private panels as the sole determiners of what is dangerous, and the proper remedy of what it or they deem improper speech.

Conservative commentators decry “Cancel Culture” and attack social media outlets for what they say is unfair treatment limiting conservative voices – even when such restrictions are applied to such things as clear misinformation about the effects of COVID-19 vaccinations. Liberal voices want bans on right-wing posts as racist and advancing white supremacist ideas, failing to recognize what Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson noted in the late 1940s: We sometimes need to hear ideas we find repugnant if only to be better armed to refute them.

There are other good reasons to wish the 24/7 omnipresence of social media could be restrained: So-called “revenge porn,” instances in which family members must endure over and over reposted public images or videos of loved ones insulted, assaulted, or killed. And then there are the kinds of societal dangers noted in a just-declassified report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), which found evidence that Russia and Iran both attempted through online tactics to influence public opinion during the 2020 presidential election.

What to do? Some solutions are relatively benign and hold great promise. Fostering competition in the social media sphere – either by funding startups or use of anti-trust laws – will reduce the power and impact of a few dominant Big Tech firms. Some social media companies already have taken steps to eliminate the financial rewards for posting blatant misinformation designed to produce as many “clicks” as possible.

Public pressure, even if it’s after-the-fact, also produced results more quickly than would moves by government regulators – and can serve as an instant barometer of public opinion. Racially-rooted jokes largely are absent in open society today not because a law was passed, but because the jokester finds quick disapproval – and for some, commercial, social or political consequences.

We have found ways in laws openly arrived at and tested openly in the courts to prevent – or at least punish – speech deemed harmful. We can file lawsuits over defamatory remarks and the authorities can prosecute conduct spurred by “fighting words” that are outside First Amendment protection.

There are ways to draw the fine First Amendment lines between repugnant ideas and illegal conduct: The Supreme Court has ruled that cross-burning can serve as an emblem of racist views and thus be protected speech but becomes criminal conduct when the intent is to intimidate a person or group.

Hard to make such decisions, create such laws or draw such lines? Yes. Likely to be stop-start, one-step-forward-at-a-time path to a workable system? Again yes. Likely to fall short at times and be frustratingly slow even in success? Almost assuredly. And in the end will we need to simply take personal responsibility to question what we read, hear and see? Absolutely.

It will take that kind of creative approach, deep engagement, constant vigilance and frequent revision and revisiting if we wish to stop short of some kind of proposed instant cure like a national speech czar – an impossible job, but with the real power of the government to rule for a time over what we say or post.

Gene Policinski is a trustee of the First Amendment Museum and a First Amendment scholar. He can be reached at genepolicinski@gmail.com.

Related Content

Watch our One on 1 interview with Gene Policinski.

Check out the rest of our One on 1 series: short, in-depth interviews reveal how Americans practice and value their First Amendment freedoms, and will encourage you to do the same.