The right to freedom of religion and belief is a fundamental right guaranteed to all people. It protects the right to believe the orthodoxy of centuries-old institutions and the right to believe the “heresy” that has given rise to countless denominations, sects, and interpretations of that orthodoxy. It also protects the freedom to change one’s belief — and, indeed, to leave behind religious belief all together.

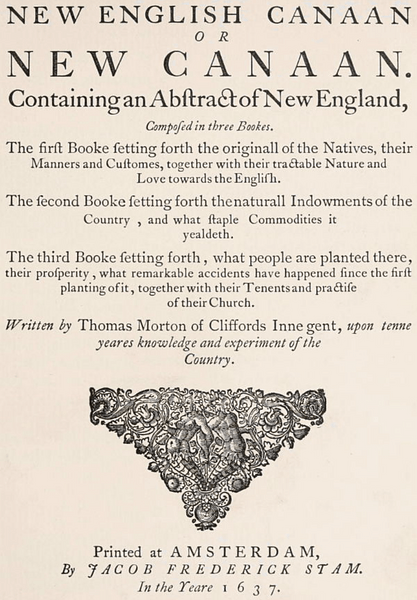

That right to freely believe according to one’s own conscience, however, was never intended to exempt religious adherents from their obligations under the law. As Thomas Jefferson wrote to James Madison in 1788, “The declaration that religious faith shall be unpunished does not give immunity to criminal acts dictated by religious error.”

Unfortunately, in recent years, this right has been viewed as fundamentally in conflict with a range of laws, policies, and other rights. As Columbia University law professor Katherine Franke recently wrote, today’s Supreme Court has elevated religious rights to a first-tier status, “while all others (such as public health, reproductive health, race/sex/LGBTQ equality) enjoy a lower constitutional status.”

“I am deeply troubled by the direction of our nation’s federal judiciary on religious matters. They have repeatedly prioritized the “beliefs” of institutions over individuals, inflexible doctrine over common-sense accommodation, and Christian hegemony over pluralism.”

We don’t need to look far to see example after example. In a recent decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of a Catholic agency seeking to discriminate against prospective adoptive and foster parents in Philadelphia because of their sexual orientation. In multiple cases related to bans on large gatherings at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Court sided with churches over lawmakers and public health officials, holding that because liquor stores and other retail shops could be open, so too could churches. And in Hobby Lobby, the Court decided that at least some for-profit corporations must be exempt from regulations to which they hold a religious objection.

In all of these cases, the “right” afforded to religious organizations placed a direct burden on others: couples seeking to adopt (and young people waiting for a home), the community as a whole seeking to control a raging pandemic, and women needing birth control who happen to be employed by a craft store.

This burden shifting comes at a cost. As the population of the United States becomes both increasingly secular and more religiously diverse, these decisions are increasingly out of step with the views of the vast majority of Americans — including those of religious Americans. According to a 2021 poll from PRRI, 77% of Americans oppose allowing taxpayer-funded adoption and foster care providers to discriminate, and 62% believe companies should be required to cover contraception.

These burdens are increasingly being borne by those who can least afford to look elsewhere for services and resources. In the closing days of the Trump Administration, a range of agencies, including the Departments of Health and Human Services, Veterans Affairs, Education, and others, rolled back rules that required religious providers, which receive billions of dollars in federal tax dollars annually, to take steps to protect the rights of service recipients, instead choosing to elevate the rights of the religious providers. Previously, the rules had required that providers inform recipients of their rights, including their right not to participate in religious activities as a precondition of receiving benefits. This common-sense provision ensured that no one — whether Christian, Jewish, Buddhist, atheist, or any other religious perspective — would be coerced into religious worship that was incompatible with their own beliefs.

Our government’s reliance on private, often religious, entities to provide essential services with government funding like adoption and foster care, housing for people experiencing homelessness, food aid for the hungry, and substance abuse treatment, means that these entities’ choice to discriminate — or condition their assistance on beneficiaries’ participation in religious programming — is no less an abridgement of the freedom of religion and belief of individuals than if it were our own government doing the same. In rural counties, these religious providers are often the only option available. But geography shouldn’t dictate which fundamental rights are available to us.

I am deeply troubled by the direction of our nation’s federal judiciary on religious matters. They have repeatedly prioritized the “beliefs” of institutions over individuals, inflexible doctrine over common-sense accommodation, and Christian hegemony over pluralism.

It’s my hope that members of the Supreme Court — and some of the loudest voices in the debate about religious freedom — come to recognize that this distorted vision of “religious freedom,” a universal opt-out from any law religious organizations don’t like, threatens the rights of all Americans and would be unrecognizable to Jefferson and the framers of our Constitution.

By Nick Fish, president of American Atheists, a national organization that defends civil rights for atheists, freethinkers, and other nonbelievers; works for the total separation of religion and government; and addresses issues of First Amendment public policy. Fish has spent more than a decade organizing and advocating on behalf of atheists and other non-religious Americans.